Number-Driven Startups: Why Unit Economics Matter

There has been a lot of talk about unit economics lately and the reason is that they are sufficient to make or break a startup’s long term journey. In simple terms, unit economics look at the direct revenues and costs associated with the most basic element of a company’s business model. For example, if you are selling shoes online, then each pair sold by you is the unit.

Let’s see why unit economics gained such importance with the story of Pets.com- a startup whose downfall was as magnificent as its rise. Founded in the latter half of 1998, the online marketplace sold pet products and based its progress on the assumption that their model was operationally cheaper and more convenient for customers. And so started their story of growth, raising millions of dollars from investors and spending huge amounts in marketing to attract their customers. To put this in perspective, their Super Bowl commercial came at a hefty price of $1.2 Million!

All this while, they were getting customers but at a considerable cost. Not only were they selling low-margin products, but also not witnessing the surge in demand they expected. The result? They were burning more cash than they were bringing in, and scaling the startup further was making it worse. By the end of 2000, they had lost a whopping $300 Million of investor money and were forced to shut down.

The lesson? Unit economics just can’t be ignored. They deserve your attention from the early stages of starting up. Had Pets.com paid heed to their unit economics earlier, we would probably be talking about a very different story today.

The two keys to driving profitability – COCA and LTV

At the heart of unit economics are two concepts which are integral in determining the profitability of the business.

The first one is COCA or Cost of Customer Acquisition which measures the money spent by a company to acquire one customer. You may be allocating resources to hire a sales team, setting up distribution channels, digital marketing, advertisements etc. to onboard new customers, so all such expenses are taken into account while calculating the COCA. The second element is LTV or Lifetime Value which is an indicator of the average amount of revenue each customer brings in during his/her association with the company.

Common sense suggests that the LTV must exceed COCA at all times for the company to be profitable. If your customer is bringing you monetary value over what you spent to get him/her on board, you’re in the safe territory. However, if you’re burning more than what you’re getting, you need to rework your strategy.

What Drives the LTV?

It is necessary to estimate the LTV of customers in order to understand whether enough cash is being brought into the business. While there are multiple factors that affect LTV, here are a few of the major ones:

- Transactional Revenue: If you are charging a one-time upfront amount for your product or service, it counts as a transactional revenue. In this case, you have to be sure that your product quality is good enough for the customer to come back to you time and again.

- Recurring Revenue: If you have a subscription model or repeat consumable purchases (such as selling razor blades which need to be bought repeatedly), you can call them your recurring revenues. Although it is easier in this case to calculate inflows, startups must make sure that customers want to stay with them for a longer time.

- Upsell: When you create opportunities to sell more to your customers- any additional products or quantities, it is called an upsell. The more successful you are at upselling, the greater your LTV will be.

- Gross Margin: Very simple, the gross margin is the product price minus production cost. It does not include operational expenses (opex) like marketing/sales costs or administrative costs. Having good margins will give you the upper hand with your LTV.

- Stickiness: Out of all your revenue streams, those customers that stick to paying you a recurring fee add to the LTV. It is also called the retention rate which can be measured in monthly or yearly cycles.

- Product Lifetime: It measures how long a product will keep serving/fulfilling the needs of the customer before it needs to be replaced by a new one. Depending on your range of products/services and their prices, the LTV can be high or low. An additional metric here is the “next product purchase rate” which is the percentage of customers who go on to buy that replacement after the initial product’s lifetime is complete.

What is the Magic Number?

The truth is that the ideal values for COCA and LTV will be different for each industry and type of business. A SaaS company will have values very different from those in the e-commerce space, and B2B numbers will remain independent of the B2C ones. So, no magic numbers exist for COCA or LTV that are applicable across the board.

But there is (somewhat) a magic ratio.

Experts suggest that on average, every customer should bring at least three times more money to a company when compared to the amount spent on acquiring him/her. This means that ideally, the CAC:LTV ratio should be equal to or in excess of 1:3. Most major companies can hit and improve this ratio as they scale, making their business profitable.

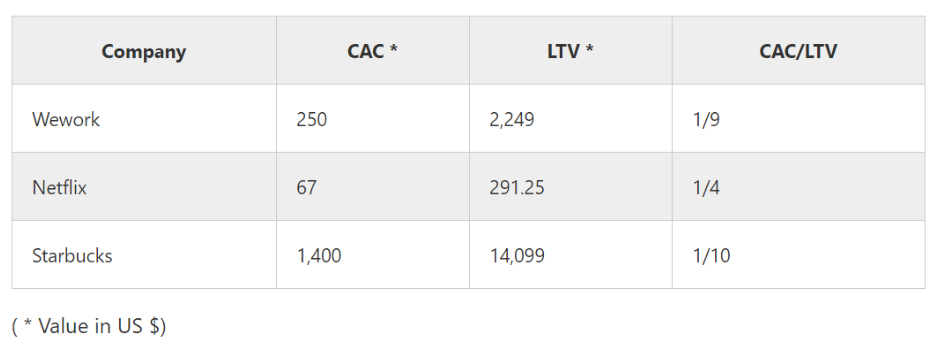

Here’s how the CAC:LTV ratio looked like for some unicorns in the recent past:

Source: https://www.tractionwise.com/en/magazine/unit-economics/

As is evident from the table above, WeWork, Netflix and Starbucks were successful in maintaining a great CAC:LTV ratio, ensuring that they were bringing more cash to their business. While WeWork has stumbled a little, the other two are growing from strength to strength.

How Regularly Should These Metrics be Tracked?

Again, there is a lot of subjectivity when it comes to tracking both these metrics. In some industries, the values of COCA and LTV frequently fluctuate, implying that founders must assess them quite often to keep up and take corrective action where necessary.

On the other hand, some sectors have relatively stable values and do not require frequent monitoring. This does not mean that the focus should shift away from unit economics. It just means that they can be looked into and acted upon after slightly longer durations.

Importance to the Investor

There is no way you can escape your numbers when you raise funds. At early stages, it might be an overstretch to track and extract positive economics but while you raise growth capital, the VCs usually prefer businesses with profitable metrics. You must exhibit how you can move towards acquiring customers at a lower cost while extracting more revenue from them.

There is a little chance that the startup with poor economics will last long, build any sustainable growth or provide a favourable exit opportunity without raising rounds after rounds of external capital.

Summing it up

It can be easily judged from the above points that positive unit economics is the key to profitability for any startup. They need to be tracked from an early stage because you won’t realise when it becomes too late. In a dog-eat-dog world, the most subtle way to leave your competition behind is to ensure that you are in control of your profitability and scale plans.

Let’s end with another example. Groupon’s success is debatable, but its failure to ascertain its unit economics is not. Groupon was in the limelight for a long time just like Pets.com and gained significant attention from investors. But after scaling, without enough focus on unit economics and increasing competition, it was burning loads of money just to retain its market share. While Groupon’s fate was not as bad as Pets.com, this story would have also been different if unit economics were taken into consideration from the early stages.